Diese Ausstellungsrezension wurde zuerst am 21.6.2025 auf HSozKult veröffentlicht. Sie geht aus einer Kooperation zwischen HSozKult und infoclio.ch hervor und wurde redaktionell von Eliane Kurmann betreut.

Agnes Gehbald, Ausstellungsrezension zu: Naming Natures – Natural History and Colonial Legacy, 15.12.2024 - 18.08.2025 Neuchâtel, in: H-Soz-Kult, 21.06.2025, https://www.hsozkult.de/exhibitionreview/id/reex-154874>.

Guinea pig, cochon d’Inde, Meerschweinchen (Cavia tschudii, named after a Swiss naturalist): the sheer variety of misleading names for a single animal reveals how language, classification, and power intersect. The temporary exhibition Naming Natures: Natural History and Colonial Legacy, currently on display in the Neuchâtel Natural History Museum, explores the 19th-century politics of naming in natural history and its deep roots in colonial structures. At the heart of the exhibition is the museum’s collection of over a thousand animal specimens, sent from South America to Switzerland in the mid-19th century. These animals were hunted, killed, dissected, catalogued, and named by Swiss naturalist Johann Jakob von Tschudi (1818–1889), with no acknowledgement of Indigenous expertise or preexisting names. The exhibition critically examines how von Tschudi’s scientific work contributed to the appropriation of Peru’s natural heritage under the guise of European scientific discovery and ended up in the Swiss museum collection.

Aligned with broader debates on colonialism and coloniality, such as those surrounding the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, and in parallel with a series of exhibitions across various Swiss museums, Naming Natures makes a timely contribution to the ongoing discussion regarding the formation of historical collections and Switzerland’s colonial past without colonies.1 Based on the research conducted by historian Tomás Bartoletti (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, ETHZ Zurich) and co-curated by artist-researcher Denise Bertschi (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne, EPFL), the bilingual exhibition Naming Natures interrogates the Neuchâtel Natural History Museum’s collection. Through a blend of natural specimens, historical objects, and archival material, all juxtaposed with contemporary art and video installations by more than a dozen mainly Latin American artists, the exhibition in Neuchâtel offers a multilayered museum visit. Its carefully grounded combination of history, artistic intervention, and innovative museography makes Naming Natures an instructive and involving examination of past colonial entanglements, questioning our current understanding of nature.

Image 1: Exhibition entrance with art piece by Danitza Willka and María José Murillo, Kawsaq salqa Pacha, 2024, hand-woven textile, 140 cm × 115 cm © Natural History Neuchâtel (MHNN)

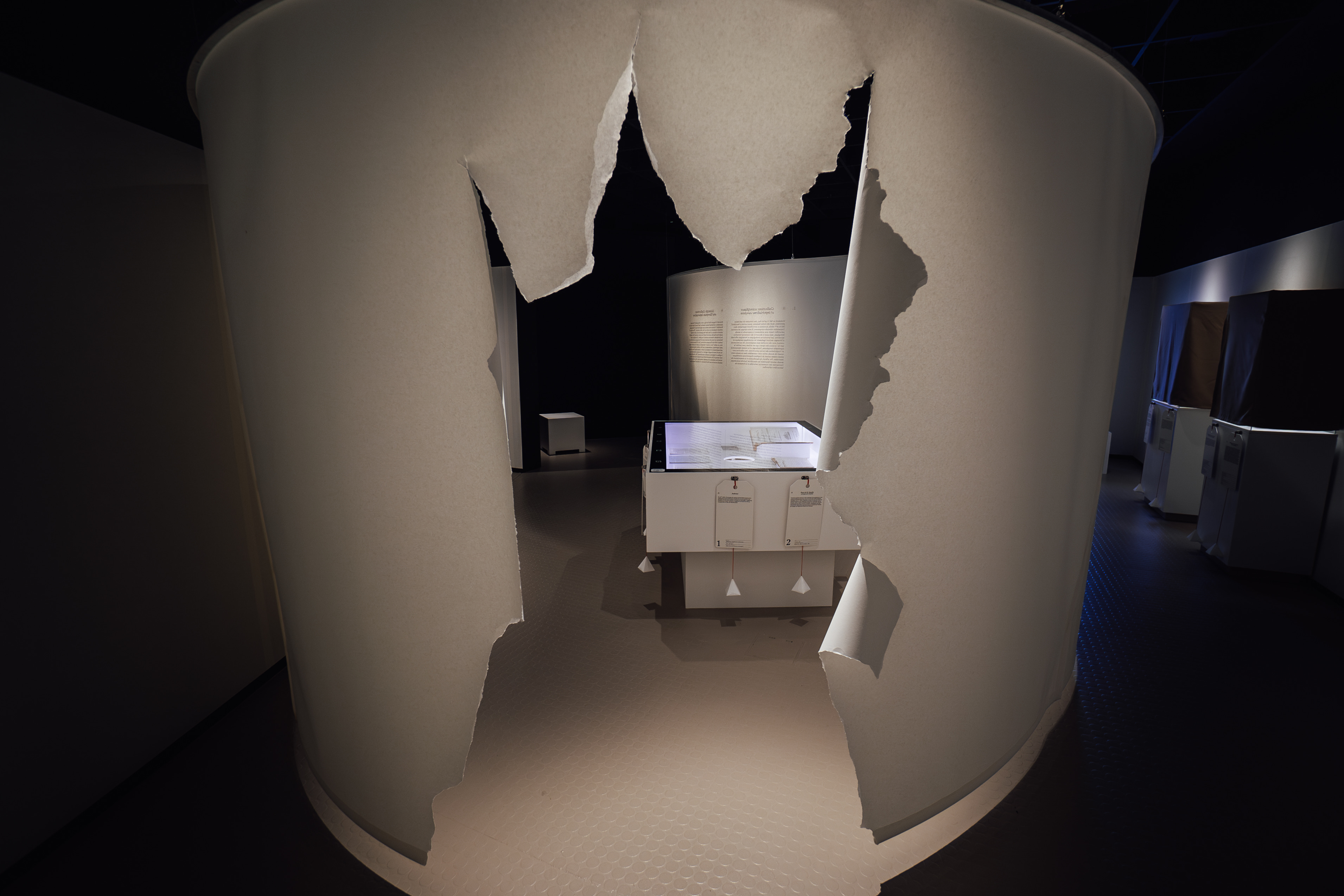

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors encounter a soundscape and a colorful, vibrant tapestry depicting animals and cultural symbols. The sound installation features voices in 41 Indigenous languages, each proclaiming the 1562 phrase of resistance against colonization: “No vamos a desaparecer / We will not disappear”; the installation is the work of artist Marco Herrera Fernández. Using a traditional Andean cross-knit looping technique for their textile art piece, Danitza Willka and María José Murillo weave together cultural narratives that challenge the portrayal of the hunted animals in Johann Jakob von Tschudi’s scientific work – animals that reappear in the following rooms. The exhibition is organized into five thematic sections: Legacy of an Expedition to Peru (room 1), Scientific Collections and European Imperialism (room 2), Johann Jakob von Tschudi's South American Expedition (room 3), Names that Speak Volumes (room 4), and New Perspectives on Natural History Collections (room 5). While there is unfortunately no exhibition catalogue, a printed leaflet available at the entrance offers context, including a timeline and a glossary with key terms from Colonialism to Scientific Racism.

Named “the Swiss Humboldt”, Johann Jakob von Tschudi drew inspiration from the Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) and his celebrated South American expedition. In 1838, at the age of 20, von Tschudi was sent by the Natural History Museum of Neuchâtel on a global voyage aboard a merchant ship. The journey, co-financed by a banking family from Geneva, aimed to promote the products of Swiss manufacturing such as clocks on the international stage: the global capitalist context underpinned scientific exploration at the time. However, instead of completing a world tour, von Tschudi remained in Peru for five years. This marked the first of three expeditions he would undertake to South America, during which he explored Peruvian zoology, Quechua ethnolinguistics, and archaeology. Unlike his role model Humboldt, who cultivated a more nuanced view of the world, von Tschudi embraced notions of racial and cultural superiority.

The exhibition criticizes portrayals of naturalists like von Tschudi as heroic figures and victorious conquerors for knowledge, whose collections have long been celebrated as achievements of European science. Such portrayals neglect and erase the environments from which the specimens were taken. A collage by Uriel Orlow poignantly critiques this legacy. Using illustrations from von Tschudi’s Fauna Peruana (1844–1846), the artist excises the animals, leaving only the blank spaces. These voids draw attention to what is missing and invite viewers to reflect on the absence at the heart of European extractive scientific practices. Likewise ignored in the narratives about “scientific heroes” are the contributions of Indigenous people, whose expertise and labor were crucial to these expeditions and for whom the animals and landscapes held vital meaning. This observation by historical scholarship applies as much to Humboldt as to von Tschudi: both were skilled networkers and collectors who often failed to credit the Indigenous collaborators, rivals, and knowledge systems that informed their work, as to do so would have challenged the myth of the solitary genius who invented “nature”. .2

Image 2: Exhibition wall with art collage by Uriel Orlow, Flora Peruana, 2024, 21 archival pigment prints based on illustrations of Johann Jakob von Tschudi's publication (1844), collage, 30 × 40 cm each © Tomás Bartoletti / Natural History Museum of Neuchâtel (MHNN)

In concert with European colonial expansion, vast numbers of plants and animals from different parts of the world were described and named following the system of binomial nomenclature. While common names vary across cultures and languages, scientific names are standardized and singular. As the exhibition demonstrates, this act of naming was rarely neutral, but reflected power dynamics, gestures of appropriation, and colonial worldviews. Behind grey curtains that visitors are invited to lift, a range of stuffed animals from birds to monkeys to vicuñas lie waiting to be revealed. In some instances, due to conservation concerns, an illustration from von Tschudi’s Fauna Peruana or a photograph replaces the specimen. Detailed information about the animal names is presented on tags attached to the vitrines. These labels show each scientific name, provide a selection of local names, and offer context such as the collection date and legal status of acquisition. Some names recount complex histories: von Tschudi named the violet-fronted brilliant hummingbird (Trochilus otero) in honor of the Peruvian military officer Otero, who assisted him during the expedition. Another bird, the yellow-rumped cacique (Cacicus cela), known as the tsirotsi and revered by the Asháninka people, illustrates his disregard for Indigenous spiritual values: he killed this sacred bird to add to his collection. As the exhibition reveals, the collection’s context was shaped not only by scientific endeavor, but also by personal bonds, violence, and illegitimate dispossession.

Image 3: Common names in question, exhibition vitrine with guinea pig © Tomás Bartoletti / Natural History Museum of Neuchâtel (MHNN)

Provenance research into natural specimens and museum objects underscores the ongoing need for critical investigation, as well as museums’ responsibility to communicate about their own histories. One striking example is a small silver llama figurine, whose display reveals how von Tschudi knowingly violated legal protections in pursuit of his private collection (the export of Peruvian archaeological artifacts had been prohibited since 1822). The silver llama entered the von Tschudi family estate before being donated to the Historical Museum of Bern in the 20th century. A similar story of illegitimate collection surrounds the stone statuette of the Andean deity Ekeko, which von Tschudi stole during a later journey in 1858. The object remained in the Historical Museum of Bern for over a century until, in a restitution process conducted a decade ago, it was returned to Bolivia. While the natural specimens may not be subject to the same legal frameworks for restitution as cultural artifacts, the exhibition critically examines the origins of the collection in Neuchâtel and questions the conditions in which it was assembled.

Image 4: View of the exhibition room with objects in curtained vitrines and interactive explanations © Tomás Bartoletti / Natural History Museum of Neuchâtel (MHNN)

By putting “nature” in the plural, the curators of Naming Natures aim to demystify the figure of the naturalist and deconstruct his role in collecting as well as naming so-called “unknown” nature. While the exhibition does not propose renaming the animals or abandoning the study of naturalists like Johann Jakob von Tschudi, it encourages a more critical awareness of the collaborations, illegitimate practices, and power imbalances that shaped the expeditions, particularly the asymmetries between Indigenous knowledge systems and dominant Western science. This art–science exhibition offers a convincing contribution to public discourse on the conflicted histories of natural history museums and the processes behind the construction of scientific collections. Through innovative approaches to postcolonial museography, Naming Natures invites reflection on processes of knowledge formation and the need to integrate Indigenous perspectives into our understanding of nature.

Notes

1 Humboldt Forum: «Kolonialismus und Kolonialität» Berlin, https://www.humboldtforum.org/en/colonialism-and-coloniality/. Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum: «kolonial. Globale Verflechtungen der Schweiz», Zürich 13.09.2024–19.01.2025, provides a line-up of current and past exhibitions in Switzerland, see https://www.landesmuseum.ch/kolonial#andere-ausstellungen.

2 Mark Thurner and Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra. “Introduction: Under Humboldt’s Footsteps,” in: Mark Thurner and Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra (eds.), The Invention of Humboldt: On the Geopolitics of Knowledge, London 2023, p. 1–13, here p. 4. Tomás Bartoletti. “Hunting and Masculine Knowledge: A Swiss Naturalist in South America and the Coloniality of Nineteenth-Century Science”, in Isis 115:4 (2024), 776–798.