International conference, University of Lausanne (Switzerland), 22–24 April 2026

Since the theoretical debates that first emerged in the 1960s and subsequent foundational studies (Goffman 1961, Foucault 1975, Perrot 1980, Ignatieff 1980) which launched lasting interest in the topic of prisons, various perspectives have expanded our understanding of carceral institutions and confinement practices. The influence of social history and microhistory, as well as the spatial and archival turns, has allowed historians to open new fields of research into the topic and to explore new sources. In particular, the significant shift from a broader analysis of punishment institutions to a focus on “prison experiences” (Spierenburg 1991) has shown the potential of carceral and penal institution archives to reveal aspects of everyday prison life (e.g., Geltner 2008, Gibson 2019, Muchnik 2019, Abdela 2019). Recent studies have advocated focusing on prisoners’ experiences and trajectories (Abdela 2023, 2024), using archival sources to uncover ordinary, daily events such as diet, the spread of disease, interpersonal relationships, riots, and escapes. And yet, even though objects and things are central to confinement experiences, the materiality of confinement remains largely understudied (Abdela 2024), except in a few studies (e.g., Carr 2025, Cassidy-Welch 2001, 2011). Confinement is defined by walls that separate individuals from society; these walls act as a spatial and administrative infrastructure which limits inmates’ physical or mental contact, both with the outside world and within the space of the institution itself. Beyond the mere walls, daily interactions between confined individuals, institutional authorities, and staff are largely paved and defined by a variety of things: food, water, books, graffiti, clothes, money, letters, official registers, medicine, punishment objects, etc. In this regard, and drawing on the material turn in history since the early 2000s, things – whether “tangible” things physically available to historians or “textual” things described in written sources (Lester 2024, 191) – might offer an additional perspective on the history of confinements more broadly, especially when addressing forms of “prison before the prison” (Peters 1995).

The international conference “Materiality and Confinements in the Medieval and Early Modern Eras: Objects, Actors, Experiences” examines confinements through the lens of their materiality. Drawing on a recent historiographical broadening of the field (Claustre, Heullant-Donat, Lusset and Bretschneider 2011, 2015, 2017), the conference aims to address various forms of medieval and early modern confinement, both judicial and non-judicial: prisons, galleys, hospitals, workhouses, cloisters, monasteries, and the like. At the same time, it seeks to reflect on methodological questions pertaining to material history as an approach and to the sources that underpin it. “Material culture”, as Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello summarised, “encompasses more than simply material objects. Objects have meanings for the people who produce and own, purchase and gift, use and consume them. Material culture therefore consists not merely of ‘things’, but also of the meanings they hold for people” (Gerritsen & Riello 2021, 3). At the same time, one might add, they also carry a socio-economic dimension. Materiality might therefore open new ways of approaching and narrating the history of confinements, revealing “other registers and ways of knowing beyond the intellectual and cognitive” (Lester 2024, 203).

Contributions are encouraged that reflect on how material history and its sources could contribute to a better understanding of different institutions of confinement and their actors (confined individuals, monks, jailers, doctors, suppliers…), practices, and infrastructures. Indeed, as “the goal of the study of material culture is primarily to understand how people use the material world available to them” (Auslander 2012, 354), we seek to understand what was, in fact, available to confined individuals in carceral, cloistered, or hospital environments and how they acted with or towards a variety of objects, artifacts, and things across the different eras. Furthermore, in most cases, confined individuals have not left egodocuments behind and the archival sources thus do not provide personal written perspectives on their imprisonment, internment, or reclusion experiences. We thus aim to explore the extent to which focusing on materiality might offer divergent/additional information, whether described in written sources or available in other kinds of material records. Is there a difference between “textual” and “tangible” things? Finally, we wish to explore whether there are any specificities to confinement things that set them apart from similar “things” in other settings. We seek to bring together contributions that address different phases of the history of confinements: for instance, the ecclesiastical practices of detrusio in monasterium and immuratio (from late antiquity to the 13th century in particular), the major shift in civil law in the 16th century which marked the crystallization of centuries of canonical penal praxis influence, or the introduction of a correlation between the seriousness of the offence and the length of the prison sentence that came to characterize early modern prisons. The conference will therefore provide an opportunity to discuss the evolution of confinement across the medieval and early modern periods, to identify possible changes, turning points and continuities across these eras, and to draw comparisons.

We welcome proposals related (but not limited) to one or more of the following research areas:

- Everyday life and sociability

Whether in prisons, hospitals, or convents, objects are used, exchanged, made, repurposed, allowed, forbidden: from books to food, work tools, letters, money, or beds, objects inform and impact everyday experiences. Recent studies have suggested that things “have the capacity… to shift social relations” (Lester 2024, 197). We welcome contributions on the materiality of everyday life and sociability. To what extent do things represent or affect confined individuals’ social lives (or lack thereof)? How do they impact their day-to-day agency? This research area might include various aspects of everyday life, from labour to spiritual exchanges, including the question of time in confinement. Contributions might also question the role that materiality played in sociability between inmates as well as with the various actors of confinement, both within and outside the walls – including visitors and confined individuals’ networks of solidarity.

- Confinement spaces

While the question of the spaces of confinement has attracted some recent attention from historians in the wake of the spatial turn (e.g. Charageat, Lusset, and Vivas 2021), it nevertheless remains widely understudied in history (Abdela 2024, Bretschneider 2017) when compared to the more abundant research in the fields of sociology or geography (e.g. Milhaud 2017). We welcome contributions focusing on the materiality and material culture of confinement spaces. This includes both the spaces within the walls – including the impact of architecture on confined experiences and the role that things play in the spatial separation (or lack thereof) of various confined populations – and around the infrastructure. This research area might question the architectural specificities of the medieval and early modern eras; for example, the adaptation of cloisters and the like to incarceration/penal purposes or the spread of specialised prison spaces for different social groups, crimes, genders, or ages. As both medieval and early modern confinement spaces were characterised by their porosity, contributions might also question connections between the inside and the outside (e.g., through the mobility of objects, such as letters) and activities that take place outside the walls, such as (forced) labour, economic transactions, family or church visits, or recovery leaves.

- Administration and the transmission of knowledge and skills

Medieval and early modern confinement institutions were closely connected to the outside world on various levels, first and foremost administratively and financially (Bretschneider 2008). From the keeping of prison registers to the bringing of food and the provision of beds, things were at the heart of keeping confinement institutions operational. How might materiality inform us about the way that these institutions were economically, socially, or politically embedded in the societies to which they belonged (Abdela 2024)? Contributions might reflect on the concrete, day-to-day material running of the institutions and their actors (including merchants, entrepreneurs, or craftsmen) or on the administrative knowledge necessary to run them. The materiality of institutional archives and their preservation is also an important consideration. Furthermore, prisons, convents, hospitals, and other institutions of confinement were filled not only with knowledge and skills carried by various actors (doctors, priests, jailors), but also with things pertaining to that knowledge and skills: “an object’s materiality conveys myriad intersecting forms of knowledge” (Lester 2024, 187). What do things reveal in terms of knowledge and skills transmission within the walls and beyond? To what extent did confined individuals themselves produce knowledge? Contributions might focus on various types of knowledge and skills, including prison writings, medical skills, religious knowledge, work-related knowledge, and the like, whether carried into confinement or acquired there.

- Power relations and violence

The vast majority of sources for the history of confinement were produced by institutional authorities. This conference aims to reflect on the potential of materiality to provide a perspective from below on individual experiences. Contributions might focus on confrontations with authority (for example, in terms of prison escapes, punishment, various cases of violence, etc.) and how objects framed power relations in confinement. As recent studies suggest, things likewise might construct and deconstruct social statuses (Cerutti, Glesener, Grangaud 2024). When it came to prison escapes, uprisings, or punishments, what role did the things available to inmates play in granting individuals their freedom? Contributions might also focus on the extent to which things defined the way in which authorities regulated confinement institutions (through violence and punishment, for instance).

We welcome proposals based on various types of tangible and textual sources (material, written, iconographic, archaeological) that focus on various confinement institutions and populations from across the medieval and early modern world (up to but not including the revolutionary era). Proposals focusing on gender, religious, and social differences, as well as underexplored regions of the world, are especially welcome.

Keynote speaker

Sophie Abdela, Professor at the History Department of the University of Sherbrooke, Canada

Scientific committee (in alphabetical order)

Frances Andrews (University of St Andrews), Pascal Bastien (Université du Québec à Montréal), Falk Bretschneider (EHESS, Institut franco-allemand de sciences historiques et sociales de Francfort), Christian G. De Vito (University of Vienna), Joachim Eibach (University of Bern), Laurence Fontaine (EHESS), Anne Gerritsen (University of Warwick), Guy Geltner (Monash University), Johan Heinsen (Aalborg University), Marie Houllemare (Université de Genève), Élisabeth Lusset (Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne), Mary Laven (University of Cambridge), Ludovic Maugué (Équipe Damoclès, Université de Genève), Vincent Milliot (Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis), Renaud Morieux (University of Cambridge), Natalia Muchnik (EHESS), Xavier Rousseaux (Université catholique de Louvain), Riccarda Suitner (Ludwig Maximilians University Munich), Mathieu Vivas (Université de Lille).

Practical information

The working languages of the conference will be English and French.

The conference will be held in person at the University of Lausanne. We will submit a funding application to the Swiss National Science Foundation to cover participants’ travel and accommodation costs.

We aim to publish selected papers in a thematic issue of a peer-reviewed international journal or in an edited volume with an international publisher.

Submission procedure and dates

22 September 2025: Please send your proposal to nathalie.dahn-singh@unil.ch. Proposals (max. 350 words) should include a title, a clear research question, and a short bibliography. Please provide a short bio-bibliographical text as well (max. 150 words).

Early November 2025: Notification of proposal acceptance

Organisers

Dr. Nathalie Dahn-Singh, University of Lausanne: nathalie.dahn-singh@unil.ch

Dr. Anna Clara Basilicò, FBK – Istituto Storico Italo Germanico: abasilico@fbk.eu

Please do not hesitate to contact us for any questions pertaining to this Call for Papers.

Veranstaltungsort

Zusätzliche Informationen

Kosten

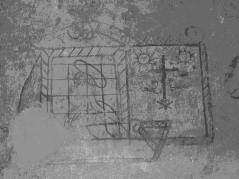

Graffiti, prison de Sermoneta (Castello Caetani), XVIe-XVIIe siècle. © Photo : Anna Clara Basilicò